The Atlantic Ocean is far more than a vast expanse of blue—it is a driving force behind the formation and evolution of hurricanes that impact the Caribbean and the United States. These powerful storms emerge from a complex mix of oceanic warmth, atmospheric instability, and dynamic weather systems. This article delves into the many ways in which the Atlantic Ocean shapes hurricane development, the mechanisms behind these tropical cyclones, and the implications for communities in the Caribbean and along the U.S. coastlines.

Unpacking Hurricane Formation

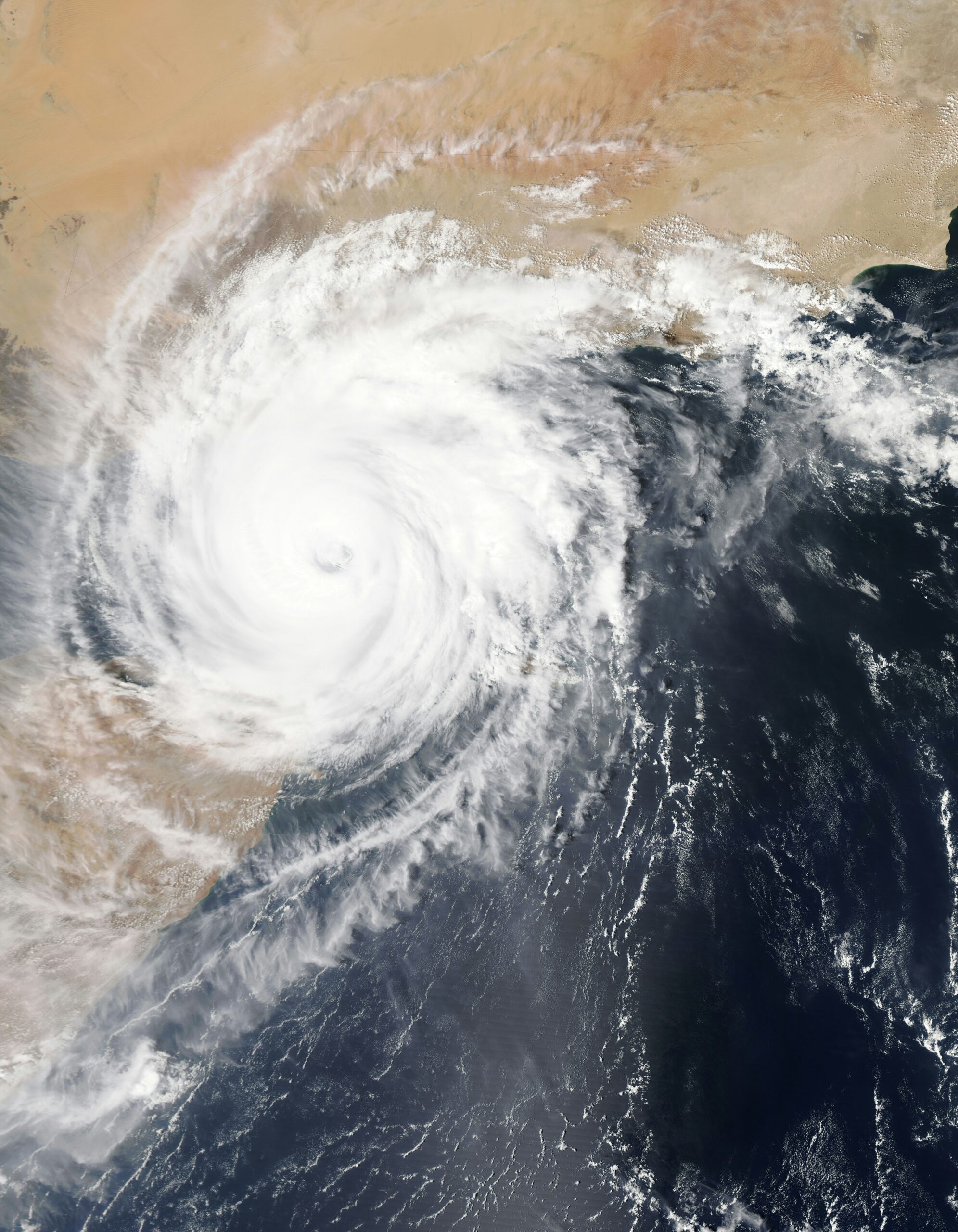

To understand the influence of the Atlantic Ocean, it is important to first grasp how hurricanes form. Tropical cyclones, or hurricanes when wind speeds reach 74 mph or more, are structured systems defined by an eye at the center, a surrounding eyewall, and spiral rainbands. Their formation typically unfolds in several stages:

- Tropical Disturbance: A disorganized cluster of thunderstorms begins to form over warm ocean water.

- Tropical Depression: As the system organizes and a circulation develops, wind speeds remain below 39 mph.

- Tropical Storm: With further intensification, winds increase between 39 and 73 mph, and the storm is assigned a name.

- Hurricane: When the system’s sustained winds exceed 74 mph, the storm graduates to hurricane status, featuring a clearly defined eye and robust spiral bands.

The transformation from a weak disturbance into a powerful hurricane relies on a delicate balance of environmental conditions, many of which are provided by the Atlantic Ocean and its unique characteristics.

The Atlantic’s Role as a Hurricane Engine

Warm Waters: The Fuel for Storms

At the heart of every hurricane is the energy drawn from warm ocean waters. Sea surface temperatures (SSTs) play a pivotal role in initiating and sustaining the convective processes within a developing storm.

- Energy from the Ocean: When SSTs exceed about 26.5°C (80°F), they trigger intense evaporation. This evaporation loads the atmosphere with water vapor, which is essential for the storm’s energy. As the water vapor rises and condenses into clouds and rain, latent heat is released, further fueling the storm’s updrafts.

- Sustaining Convection: This continual release of latent heat is critical for maintaining the low-pressure core that drives the cyclone. Regions like the Caribbean and parts of the Gulf of Mexico provide this essential heat, making them prime areas for hurricane formation.

Oceanic Cycles and Long-Term Variability

The Atlantic does not remain constant over the years. Natural cycles and oscillations can modify its temperature and energy availability:

- Atlantic Multi-decadal Oscillation (AMO): This long-term climate pattern causes fluctuations in the SSTs of the North Atlantic over several decades. During warm phases of the AMO, the increased heat content can lead to more frequent and intense hurricanes, while cooler periods tend to have the opposite effect.

- Seasonal Variations: Seasonal changes, driven by the sun’s angle and weather patterns, also affect SSTs. Typically, the late summer and early fall are the peak periods for hurricane development when the ocean’s heat is at its maximum.

Atmospheric Instability and Moisture

While warm waters provide the fuel, the atmosphere above the Atlantic must be conducive to storm growth. Two key factors here are atmospheric instability and abundant moisture:

- Instability in the Atmosphere: A steep temperature gradient between the warm ocean surface and the cooler upper atmosphere encourages the rapid upward movement of air. This instability is essential for the vigorous convection needed to build a storm.

- Moisture-Rich Environment: High humidity levels near the ocean surface ensure that as air rises, it remains saturated. This saturation leads to the formation of dense clouds and heavy rainfall, both of which are integral to the hurricane’s structure.

Wind Shear: A Double-Edged Sword

Another important atmospheric factor is wind shear, defined as the change in wind speed or direction with altitude:

- Low Wind Shear Favors Storm Development: When wind shear is weak, the developing storm remains vertically aligned, allowing the organized structure of the hurricane to strengthen and maintain its energy.

- High Wind Shear Disrupts Development: Conversely, strong wind shear can tilt or break apart the storm’s structure by displacing the core from the surrounding rainbands. This is why hurricanes most often form in areas of the Atlantic where wind shear is minimal.

The Caribbean: A Crucible for Tropical Cyclones

The Caribbean Sea is recognized as one of the world’s most active regions for hurricane formation. Its geographical and atmospheric conditions combine to create an environment where tropical cyclones can rapidly intensify.

Strategic Geographic Positioning

- Near the Equator: The Caribbean is located in the lower latitudes, where the Coriolis effect—the force that imparts rotation to a moving system—is just strong enough to initiate the spin required for cyclone formation. This delicate balance allows storms to develop while still having access to vast reservoirs of warm water.

- Warm Currents: Ocean currents such as the Loop Current in the Gulf of Mexico and several regional currents help distribute warm water throughout the Caribbean. These currents ensure that even during brief periods of cloud cover, the sea retains enough heat to support storm development.

Abundant Atmospheric Moisture

- High Humidity: The tropical climate ensures that the Caribbean atmosphere is saturated with moisture. This high level of humidity is crucial for generating the heavy rains and convective activity that characterize hurricanes.

- The Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ): This belt of converging trade winds, which migrates north and south with the seasons, often passes over the Caribbean during hurricane season. The ITCZ provides a steady supply of moisture and can serve as the initial trigger for tropical disturbances.

Local Weather Dynamics

- Diurnal Temperature Changes: Daily heating cycles enhance evaporation during the day, further increasing moisture in the lower atmosphere. At night, as temperatures drop, the condensation process can lead to rapid cloud formation and intensified thunderstorms.

- Moisture Recycling: The relatively confined nature of the Caribbean Sea means that moisture is often recycled within the region, bolstering the intensity and longevity of tropical systems.

Storms on the Move: From the Caribbean to the U.S.

Once a hurricane forms in the warm waters of the Caribbean, its path is largely dictated by larger atmospheric and oceanic currents as it moves toward the U.S. coast.

The Role of the Gulf of Mexico

- A Secondary Energy Source: The Gulf of Mexico, with its shallow, warm waters, often acts as a secondary incubator. Storms that enter the Gulf can undergo rapid intensification due to the abundant heat and moisture available.

- Guiding Currents: The unique shape of the Gulf and its surrounding weather systems can steer hurricanes towards the U.S. coastline. The interaction between the Gulf’s warm waters and the prevailing wind patterns creates a pathway that many storms follow.

Interaction with Mid-Latitude Weather Systems

- Transition to Extratropical Systems: As hurricanes progress northward along the U.S. Eastern Seaboard, they may encounter cooler air and frontal systems typical of mid-latitude weather. This interaction can cause a hurricane to transition into an extratropical cyclone, characterized by a broader wind field and altered rainfall patterns.

- Frontal Boundaries: These boundaries, which separate warm and cold air masses, can enhance or disrupt the structure of a hurricane. In some cases, a frontal boundary may add extra energy to a storm, while in others, it may help to dissipate it.

Impacts Upon Landfall

- Storm Surge and Coastal Flooding: One of the most devastating impacts of a hurricane is the storm surge—a rise in sea level driven by the force of the winds. This surge, combined with heavy rainfall, can lead to catastrophic coastal flooding.

- Wind Damage and Inland Rainfall: Beyond the coast, hurricanes can unleash strong winds and torrential rains that damage infrastructure, cause widespread power outages, and result in inland flooding. Areas along the Gulf Coast and the Eastern Seaboard are particularly vulnerable.

Looking Ahead: Climate Change and Future Hurricane Activity

The interplay between the Atlantic Ocean and hurricane formation is not static. Ongoing changes in the global climate are influencing the key factors that drive these storms, raising questions about what future hurricane seasons may hold.

Increasing Sea Surface Temperatures

- Enhanced Energy Supply: As global temperatures rise, so do sea surface temperatures in the Atlantic and Caribbean. Warmer waters mean more evaporation and, consequently, a larger reservoir of energy for hurricanes. This trend could lead to more frequent and intense storms.

- Extended Seasons: With higher temperatures persisting later into the year and beginning earlier in the season, the window for hurricane formation may lengthen. This shift could mean a longer period during which communities are at risk.

Shifts in Atmospheric Dynamics

- Changing Wind Patterns: Climate change may alter the large-scale wind systems that guide hurricanes, including trade winds and jet streams. Modifications in these patterns can influence not only where hurricanes form but also the paths they take.

- Variations in Wind Shear: Some studies suggest that climate change might reduce wind shear in certain tropical regions, further favoring the development and intensification of hurricanes. However, the exact impact of these changes remains an active area of research.

Rising Sea Levels and Coastal Vulnerability

- Exacerbated Storm Surge: As sea levels rise due to melting ice and thermal expansion, the baseline for storm surge increases. This means that even if a hurricane’s wind speeds remain unchanged, the risk of coastal flooding becomes more severe.

- Increased Erosion and Habitat Loss: Higher sea levels also accelerate coastal erosion and can damage natural barriers such as mangroves and barrier islands. These changes leave coastal communities more exposed to the full force of a hurricane.

Mitigation and Adaptation: Preparing for Future Storms

Understanding the role of the Atlantic Ocean in hurricane formation is essential for developing strategies to protect vulnerable regions. As the climate continues to change, efforts to mitigate risks and adapt to evolving storm patterns become even more critical.

- Advanced Forecasting and Monitoring: Improvements in satellite technology, ocean buoys, and computer modeling have significantly enhanced our ability to predict hurricane paths and intensity. Continued investment in these tools is vital for early warning systems and disaster planning.

- Resilient Infrastructure: Building structures that can withstand extreme weather, reinforcing coastal defenses, and updating building codes are crucial steps to reduce damage from hurricanes. Communities in high-risk areas are increasingly adopting resilient construction practices.

- Climate Change Mitigation: Addressing greenhouse gas emissions and transitioning to sustainable energy sources is imperative for long-term hurricane risk reduction. Global efforts to combat climate change can help stabilize sea surface temperatures and mitigate some of the factors that contribute to stronger storms.

- Community Preparedness: Public education campaigns, regular emergency drills, and robust evacuation plans ensure that residents are prepared when a hurricane approaches. Community resilience is built not only on physical infrastructure but also on well-informed and prepared citizens.

Conclusion

The Atlantic Ocean plays a multifaceted role in the formation and evolution of hurricanes that impact the Caribbean and the United States. Its warm waters act as a critical energy source, driving the evaporation and convection that birth tropical cyclones. Atmospheric conditions—such as instability, abundant moisture, and low wind shear—combine with oceanic factors to create the perfect conditions for hurricane development. The Caribbean, with its strategic location, warm currents, and moisture-rich environment, serves as a fertile ground for these storms, while regions like the Gulf of Mexico further intensify and channel them toward the U.S. coastline.

As hurricanes traverse the Atlantic and approach land, they interact with mid-latitude weather systems that can modify their structure and impact. Whether it is the dramatic storm surge along the coast or the inland flooding that follows, the effects of these storms are far-reaching. Moreover, as climate change continues to warm the ocean and alter atmospheric dynamics, the intensity, frequency, and duration of hurricane seasons are likely to evolve.

Our growing understanding of these processes underscores the need for robust forecasting, resilient infrastructure, and proactive community preparedness. By continually studying the complex relationship between the Atlantic Ocean and hurricane formation, scientists, policymakers, and communities can work together to mitigate risks and safeguard lives and property.

In the end, the Atlantic Ocean is not just a backdrop but an active, dynamic player in the story of hurricane formation. Its influence is felt in every stage of a storm’s life—from its initial spark over warm waters to its ultimate landfall, where nature’s fury is unleashed. As we move into a future of changing climate patterns, appreciating this intricate interplay will be key to adapting to and mitigating the challenges posed by increasingly powerful storms.